| In 1999 I participated as a volunteer on San Pedro de Alcantara.

The site is about 90 km north of Lisbon and the archaeological team lived in an old school that is

empty over summer. During the six-week season, there were constantly 10-15 people on the site.

The wrecksite is located below some high cliffs exposed to the ocean. To facilitate diving, a

cable lift was constructed.

Surface air supply

Most investigations on the San Pedro side were static, i.e. the diver remained in the

same area. Such dives were made by SSBA. This is also known as

"hookah". An Italian Del'Air low pressure compressor was connected to a hose that branched

to two hoses, each with one regulator second stage. Thus two divers could be accommodated with

unlimited air, but any additional divers must use tanks.

Except for the cable system and the SSBA, simple basic technology was used. Excavation in sandy

trenches was made by hand fanning.

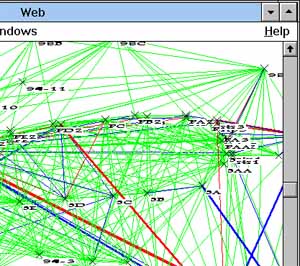

All measurements were entered in the Web for Windows program, developed by

Nick Rule. This created a 3D map of the wrecksite.

SPA99, procedure for

excavation

The diver should carry: compass, depth gauge, writing tablet, measuring tape, "goody bag" and

small plastic bags.

- Decide your excavation area.

- Make a topographical drawing (map) with magnetic north fixed. Write name & date on the slate.

- Choose a start point for your excavation.

- Move all loose stones. Try to place them on a rock bottom surface, not needing to be

excavated.

- When you reach a cavity or sand layer, sweep away loose sand carefully.

- Record any artefacts as you go down in the pit. Recover and put

all small artefacts in your numbered plastic bags, except for iron. Position the finds

by triangulating to at least 2 fixed "spits" (base

points), using a stainless steel or plastic measuring tape. Also measure the depth

(average between swell) relative to the base points.

- Encrustions/concretions containing iron objects should be recorded, positioned and

left on the site, because of the conservation problem. Only certain concretions are recovered,

after a decision is made.

- When a trench or pit is finished, replace the large stones that were moved. This is in order

to try to restore and stabilise the site.

SPA99, procedures for artefacts

- Each recovered artefact gets a sequential number since the project start. In 1999 we reached

object numbers over 4000.

- The objects are placed temporarily in individual freshwater bowls. Objects belonging to the

same find may be placed in the same bowl, as long as different metals don't mix.

- A written find report is made by the diver and stored in a sequential order. This report

contains: the artefact's number, position (triangulated from at least 2 fixed base points), depth

relative to the base points, depth into sediment, description and a very simple drawing. When

needed, a map of excavated areas is made.

- A written report of the workshift is made in the fieldbook. This can be notes of dive time,

general impressions, and referral to corresponding find reports if any. Any measured positions

will be entered in our 3D mapping system.

- Later, all objects are measured, weighed, photographed, filed and placed in separate baths

containing different conservating chemicals.

- Finally, most artefacts are dried and stored with the original object number always attached.

However, wood and iron must be kept wet until delivered to the conservation department.

The project diary is mostly written in Portuguese, and was published by our sponsor

www.netc.pt. Here are the only two days written (by me) in

English:

THE ANSWER MY FRIEND, IS BLOWING IN THE WIND

13 August

During the night we have heard the wind howling. The wind is really

talking to us. But what is the message? In the morning we go to have a look at the sea. It's too

rough to dive. Now we know what the wind was telling us: "Don't dive on San Pedro today!" It's

that simple, the weather decides when we may dive, not we.

Will we be able to dive tomorrow?

ROCK MUSIC

14 August

This morning Stéphane Gautron told us about the battle of

Aboukir in 1798. Aboukir is close to Alexandria in

Egypt. So Stéphane would know, in 1998 he was diving in Alexandria

on another project.

In 1798 England and France were fighting for the control over Egypt. The

French navy was anchored at Aboukir. No attack was expected and most of the crew were on leave on

land. Meanwhile, the English navy under Lord Nelson managed to reach Aboukir unnoticed and

attacked the anchored fleet by surprise. There was no time to load the guns so 40 French ships

were sunk and only 4 frigates escaped. The English lost no ship. Underwater archaeologists are

now investigating the remains that are hidden under the bottom sand.

A few years later the same English fleet under Nelson fought the battle of

Trafalgar. Again the English were victorious and sank among others the Spanish admiral ship

Santissima Trinidad. This 140 gun ship sank on deep water and has still not been located.

Here's the interesting detail: It was built in 1769 by Matthew Mullan, the same shipbuilder who

worked on the Havanna shipyard on Cuba where San Pedro de Alcantara was built in 1770. It's a

small world.

Waiting for the next dive, we spend the morning with the usual routine

work: cataloguing, measuring, and weighing recovered objects.

In the afternoon the weather was finally calm enough for diving. But it

was only safe to dive in the deeper areas. There we did bathymetry. That means measuring and

mapping the depth curve between two spits (i.e. fixed points). This is

an aid for us in creating a map of the seafloor.

While we were down there we heard a strange sound, "Boom ... Boom ...

Boom". That was the violent waves crashing against nearby rocks, slightly moving and rocking the

huge boulders back and forth. The sea is really talking to us today.

Continued=>

|

|

Jean-Yves Blot

The surface current can drift divers away. The solution is to dive below surface and

return to the steel wire of the cable lift.

compressor

breathing from the hose

map of a small area as drawn on the diver's slate

Such steel pins, spits, (to the right of sea star)

were fixed in the rock and used as base points for 3D positioning.

The final Web for Windows 3D map would look roughly like this.

On a calm day, Carlos Ryder draws a concretion before chiseling it off. |

Back to Nordic Underwater Archaeology

Back to Nordic Underwater Archaeology