Wasa Goes Down, Can Come Up!Despite steep initial costs, the sunken failure that was the Wasa has become a startling success attracting millions of visitors and dollars to one of Stockholm’s most unusual museums. It has been called a monument to the Swedish sense of humour. With cannons gleaming, the crown of the Swedish armada, the Wasa set off on 10 August in 1628 to teach the enemy Poles a lesson. Crowds lined the shore on the clear, almost windless day. But within minutes of starting her maiden voyage, the mighty warship suddenly sank, marking one of the biggest fiascos in Scandinavian history.

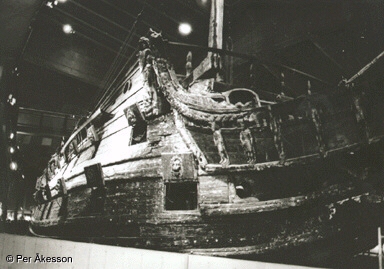

Under the bellyMajor salvage efforts didn’t get underway until 1956 when a Swedish petroleum engineer, Anders Franzén used a home-made core-sampler to locate the ship, which he was convinced was well preserved, spared from the devastation of shipworm by the cold brackish water. After divers confirmed his predictions, the government with the support of private industry began preparations to raise it. It took three years for divers to string steel cables through tunnels blasted with water jets under the belly of the 1,400-ton craft. Other divers removed the ship’s masts, spars and rigging. By pumping tons of water through two pontoons, the wires pulled taut, thereby raising the Wasa in 1961, as the TV cameras rolled and historians and archaeologists cheered. At the time it was the world’s oldest wreck to re-emerge, beating Lord Nelson’s famous Victory by 130 years. However, the trick lay not just in lifting the ship, but preserving it. Setting the vessel under the constant jets of a sprinkler system, experts invented and then applied the "glycol-method", impregnating the black oak with polyethylene glycol for 17 years to prevent it from shrinking and cracking as it dried. Some 580 tons of water evaporated, during the process.

"But most importantly," says Helmersson, "we have the opportunity to dig very deep into a precise time period." Indeed, the Wasa offers a window onto the past, illuminating the life of the 17th-century sailor and the horrible scenes of a desperate, drowning crew. Teams of archaeologists have explored every nook and cranny of the veritable time-capsule, complete with 500 sculptures and such ordinary objects, as watches, games, forks, shoes, a bible, carpenter’s tools and Sweden’s oldest clay pipes. They have also uncovered remains from 25 of the 50 men and women who went down with the ship, including the skeleton of a seaman, still carrying his leather money pouch.

"Swedes are finally discovering this period, specifically the years around 1628, which brought major changes to the society," says Helmersson. "Under Gustav Adolf II, Sweden rose to be a major power in Europe." The hundreds of displayed artefacts let alone the ship are enough to fire the imagination. Not only can kids piece together the life of a long-gone mariner – from his barber’s tools to his boots – they can build their own ships on computer screens, seeing that if the real Wasa, 69 meters long and reaching as high as 51.5 meters, had been only about 0.4 meters wider than its original 11.3, the accident probably would never have happened. For the large masts, heavy cannons and insufficient ballast made for a treacherously wobbly design. The Wasa’s belated triumph raises new questions and expectations about salvaging in the Swedish archipelago in the Baltic Sea. Historians know of twelve sunken warships from the 16th and 17th centuries, six of them not yet located. Between the cold brackish water protecting them from shipworm and the Swedish laws protecting them as national antiquities, chances look good of finding and benefiting from yet another treasure trove of history. Petter Karlsson Published in UNESCO Sources, February 1997 Related text

|

More

than three centuries later, the Wasa is once again bringing in the crowds, this time as a

major tourist attraction. Raised and restored with extraordinary technological finesse, the Wasa

is now the focus of Sweden’s only self-sustaining museum. Attracting more than 750,000 visitors

each year, the Wasa Museum of Stockholm earned a total income of five million dollars in 1996.

More

than three centuries later, the Wasa is once again bringing in the crowds, this time as a

major tourist attraction. Raised and restored with extraordinary technological finesse, the Wasa

is now the focus of Sweden’s only self-sustaining museum. Attracting more than 750,000 visitors

each year, the Wasa Museum of Stockholm earned a total income of five million dollars in 1996.

Back to Nordic Underwater Archaeology

Back to Nordic Underwater Archaeology