15

David's Wrath and the Happy End (1)

Erik's father David was made of different matter. Erik describes him as

"an artistic nature, impulsive, easily moved, intense", but without much

schooling. He and his sister Ellen attended the Army's first meeting in

Göteborg (Gothenburg, Sweden) as teenagers. He was at once attracted

especially by the joyful singing and instrument playing.

| Some years later he became a soldier and was expelled from his family

("I left their house and have never set my foot there again", he had told

Dad at one time.)

He soon became an officer and was seen and heard playing several difficult

instruments -- harp, bandonion, consertina. How he managed to learn

these instruments I do not know, as he had had no training and didn't even

know how to read written music. But then he did no virtuoso playing, but

just pulled out a few chords which very effectively accompanied his own

singing.

He could be very kind and considerate and was known as a good chief

and leader. But he could also show a temper that gave him difficulties.

It is said that his appointment to Switzerland in 1922 was some sort of

punishment, but I only know it as a rumour...

|

|

When David became angry he took to silence. The more angry the more silent

and the more dark clouds in his forehead.

For instance, while in school Erik learnt to play chess and became rather

good. In his teens he won a junior championship at the local Chess Club

in Stockholm. This meant he had to go one or more evenings a week to the

Club to play. He came home late, his clothes reeking of tobacco since there

was much smoking at the Club. David detested this, but he never said anything.

He just stayed up until Erik got home, then showed him silence and went

to bed.

Another time when Erik (with one of his first earned salaries) bought

himself a pair of shoes without consulting David, there was also difference

of opinion between them. For David shoes should be high and black -- Erik

bought low and brown. David remained silent for a long time.

But all this was nothing compared to what happened when Erik told

his parents that Frieda and he were getting married! Father David

was severely appalled, and rebuked Erik strongly. Erik was very surprised.

Both his father and his mother had liked Frieda very much. She had been

like an daughter to them. Even after Erik left for London Frieda continued

to come for Sunday afternoon coffee and a bit of gossip with Betty.

According to SA rules a Cadet was not allowed to write to someone of

the opposite sex (outside the family) while in Training. So Erik did not

write to Frieda. But he did write to his mother, who in turn reported in

full to Frieda. And there were no rules to hinder Frieda from writing to

him.

Now what was suddenly wrong with Frieda? David pointed out two things:

her age and her health. Frieda was nearly five years older than Erik. The

regulation in those days was that the wife's career must follow her husband's,

i.e. same rank, same shared ministry, same date of retirement. "Just think

of it", David told his son. "By the time you are 65 she will already have

worked over time for five years. And if you should become a Commissioner

(with a retirement age of 70) she will have to toil until 75!" Also Frieda

had had long periods of bad health in the past. How would she cope with

the strenuous life of a married woman officer?

Now such arguments have never impressed the young. Erik had never

thought much about the age difference, and Frieda seemed to be healthy

enough at the time. But the Commander of the Territory (Colonel Mary Booth)

had to consent to an international marriage of this kind (Frieda was assisting

officer at a social institution in England). David told Mary Booth to stop

this marriage, and therefore she had some serious talks with Erik.

| Did he really know what he was doing? When did he last meet Frieda?

(Since December, 1924, when Erik left Berne after the Christmas break in

Training, they had met only once, briefly, at an Officers' Staff Course

at Sunbury outside London in January, 1926. That had been more than a year

ago.)

Well, the age and health arguments were taken care of by their superiors.

Apparently these people in high positions wanted to have this matter settled.

Very unconventionally Erik was ordered to go to London (journey paid) to

meet Frieda and talk things over. Frieda's chief was Commissioner Catherine

Bramwell-Booth. She arranged for the young couple to meet at an old folks

Home in Hastings for a week. There they met, walked and talked, and at

the end of the week they had made up their minds:. Nothing was to separate

them. |

|

Mary Booth signed the application form: "Do not recommend, but cannot

very well refuse." And David went into silence. Erik and his father were

sitting at the breakfast table without a word and with the storm clouds

all around. Betty was very unhappy but did not know what to do.

Frieda was sent to Berlin and given an appointment in a Maternity Home

(Wöchnerinnenheim). She knew how to handle sturdy old fathers (had

had good practice with her own old man!). At her arrival she immediately

re-charmed David and Betty. The clouds flew away from David's forehead

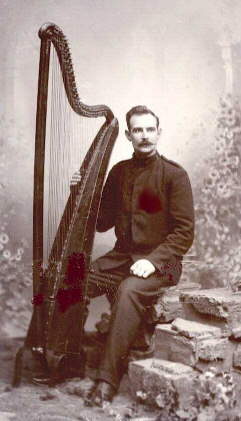

as he melted as wax. "Amazing" Erik comments. Click here for a picture

showing the result (although

taken in 1929, the picture does not indicate that David was unpleased...).

Erik and Frieda could not marry until some months later. It might have

had to do with German law or with Army rules. Dated photos show that during

this time they did some travelling and visiting. Among others are photos

from Clarens (near Montreux) in Switzerland, where they saw M. and

Mme

Perret (who will later play a role in this story). The

opening

picture in this story was taken at Chateau de Chillon near Montreux

in 1928.

Frieda came to Berlin in the fall of 1928. At about the same time David

and Betty received orders to go to Denmark, David as Territorial Commander.

The wedding did not take place until March 7, 1929.

In his unpublished memoirs Dad has written:

We rented a part of a big apartment at Cöpenicker

Strasse 49 with the family Maison, who later were to be our good friends

-- to a large extent because of Frieda's winning manners. Our apartment

had a big kitchen and a big, dark room, a so called "Berliner Zimmer."

To that a cold loggia and a dark, small chamber -- all against a gloomy

back yard. No toilet inside -- it was half a story down. No bathroom. We

got ourselves a big zink tub in which we bathed after warming water in

the kitchen.

But here we were happy, and we got on well.

In a good tale, this should be the happy end. But in real life the story

continues, for better or for worse.

Updated 1999 02 23; 03 15;

webmaster: sw@abc.se