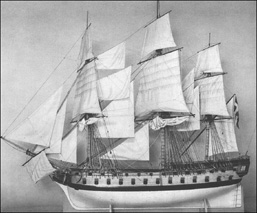

| In 1788, the Swedish navy was in good shape, recently modernised with several ships designed by

the naval architect

Fredrik Henrik af Chapman. Russia was engaged in war against the Turks, and the Swedish king Gustav III saw this as an opportunity to take back the Baltic territories lost to Russia in 1720. Thus Sweden attacked Russia. On the king's orders, despite objections from nobility and others. The actual attack was initiated by a fake attack by disguised Swedes on their own border post, giving Sweden an excuse to "defend itself".

Part of the reason for the Swedish attack may have been that the Swedish king had domestic problems and needed a "nice little war". Or maybe he was just obsessed with the idea of achieving glory on the battlefield, rather that remaining a "dull" peace-time king. The plan was to attack the Russian capital Saint Petersburg by sea. The following naval warfare included several minor and larger battles in the Baltic Sea, including a large battle off Hogland in 1788 (draw), and a smaller battle at Svensksund in 1789 (Sweden lost). Meanwhile, Denmark declared war on Sweden, making the situation dangerous for the Swedes. The decisive point came in the summer of 1790. First Sweden tried to attack Russian Navy units anchored in Reval (Tallinn), which failed. After that, Sweden and Russia fought two consecutive sea battles in the Finnish Gulf. These battles were probably the largest sea battles ever in the Baltic Sea: The "gauntlet" at Viborg BayThe first battle of 1790 (rather a breakout) was on July, 3 in the Viborg Bay. A Swedish navy unit of 400 ships (21 ships of line) was trapped in the relatively narrow bay leading to Viborg. A Russian navy unit of about 150 ships had been blocking the exit since May 22. Finally, after a month's waiting, the wind was favourable, and the Swedes broke through during the night and early morning. The major battle was near the small Dalnaya Bay. One Swedish fireship, the Postiljonen, accidentally hit the Swedish ships Enigheten and Zemira, which caught fire and sank. In smoke from burning ships and gunfire, some of the following Swedish ships lost course, hit ground, and sank. The Swedes had saved their navy but lost 7 ships of line.

Totally, at least 50 ships sank on both sides. This site is presently on Russian territory. Note to the map: Trångsund (Uuras in Finnish) is situated a little bit westwards from the marking arrow. The bigger island in the west is Uuras Island and the narrow straight between it and the smaller island in the north is actually Trångsund. Even today the sea channel to Viborg and to Lake Saimaa channel passes this very same straight. Uuras was earlier Viborg's outer harbour, mostly timber export. Today there is a Russian coast guard and naval base (or more like a collection of sunken vessels) and a small commercial harbour. Svensksund battleThe second battle of 1790, the "real battle", between the two navies took place July 9-10, at Svensksund (Rochensalm in Russian, Ruotsinsalmi in Finnish). This is located in the narrow straits of the south Finland archipelago. The Russian navy, commanded by Prince Nassau, had 14,000 men and 1200 guns on 32 larger and 200 minor ships. The Swedish navy was commanded by the king, assisted by colonel lieutenant Carl Olof Cronstedt. It had 12,500 men and 1000 guns on about 200 larger and minor ships. This Russians attacked while the Swedes were in position waiting between the skerries and islands. The attacking heavy Russian galleys had trouble manoeuvring in the rough sea. The Swedish ships, on the other hand, were waiting well anchored and shooting without problem. At the same time, small Swedish gun sloops rowed from the sides and attacked the Russians from the rear. These sloops were 20 m long rowing boats rowed by 60 men with just one 24-pound gun in the bow. They were mobile with a low profile making them very hard to hit for the Russian ships. The Russian navy was totally defeated. The Russian side lost 9,500 men (mostly prisoners) and 50-60 ships (sunk or captured). The Swedes lost 6-700 men (killed) and 6 ships. Among the lost Russian ships was the frigate Saint Nikolai, which was located in 1948. Some time after that, Sweden (having exhausted its forces) made a peace treaty with Russia where neither side lost any possessions. The Swedish objectives had failed. Despite one naval victory, the result was status quo, and a peace that lasted for nearly 20 more years. The Swedish king was assassinated in 1792 by disappointed noblemen. Note to the location map: There is an error. The red circle should be west from Fredrikshamn where the Kymi River meets the sea. Detail map of Svensksund by Hans Högman.

Investigations at ViborgDiving in Russia has taken place at the site of the battle in the Viborg Bay, since around 1983. During 1994-1996 it was a joint Russian-Swedish project named Project Aurora. In 1994 a burner ship found and in 1996 the Lovisa Ulrika was found. The Swedish contact of the Project Aurora has been Hans Mossberg, Svenska Marinskeppsföreningen, tel & fax +46-155-21 98 80.

From 1997 it is a purely Russian project, in co-operation with the "Archeoclub d' Italia". Several Russian and Swedish shipwrecks have been located and investigated. Some finds are already exhibited in the Viborg Historical Museum. This museum is located in the old Viborg Castle and can be visited by train or bus from St Petersburg. Identified Swedish shipwrecks include: The ships of line Enigheten, Hedvig Elisabeth Charlotta, Lovisa Ulrica (74 guns, found on 15 m depth), frigates Zemira and Uppland (44 guns), and the brig Dragun. Investigations at SvensksundThis site is on Finnish territory. Identified Russian ships include the galley or frigate Saint Nikolai (hull intact in one piece, but stern cabin smashed by helmet divers salvaging cannon in the 1930s, investigated from the 1950s to the 1980s). Per Åkesson, October 1998 Related links

Sources in Swedish

Literature

|

Back to Nordic Underwater Archaeology

Back to Nordic Underwater Archaeology